In 1966, Krafft Ehricke wrote and had illustrated a paper describing the next 35 years in space travel. In his view, the future would hold Orion nuclear pulse vehicles, fusion powered spacecraft, mining operations on Mercury and manned missions as far out as Titan.

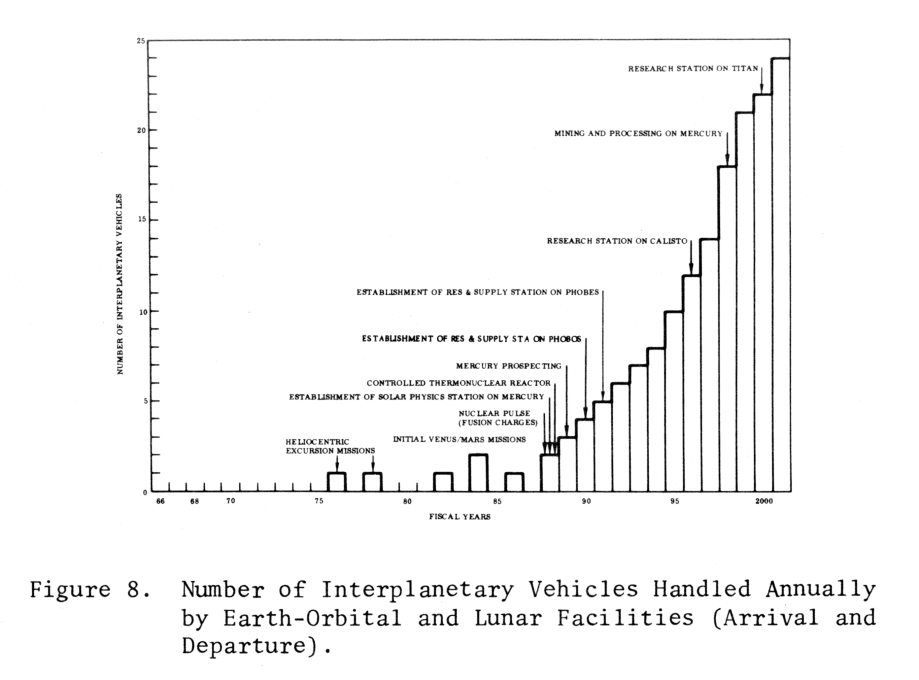

Here’s a chart illustrating the increasing number of deep-space manned spacecraft processed in Earth orbit or on the moon. Note that things really kick off in 1988, when nuclear pulse vehicles get going:

Also included were a number of poorly-reproduced paintings (is there any other kind) illustrating some of the missions, such as the establishment of a research station on a remarkably haze-free Titan in 1995:

And the landing of an expedition on “Jupiter VII” in 1997:

Ehricke got the environments wrong (he included things like manned landings on Venus), and he *really* got the timing wrong. In fact, on his chart showing missions over the next 35 years… not a single one of them, not even the smallest, has come about. But what’s interesting is not that he was wrong. What’s interesting is that a respected rocket engineer could make these predictions with a straight face and fully expect to be taken seriously. Quite possibly he did not expect that his schedule would be adhered to. But certainly he thought that some effort would be made to fulfill missions at least somewhat like these, at least somewhat on the schedule he foresaw. But within two years, the Saturn V production line would be ordered closed, and a few years after that NASA would be pulled back from the exploration mission entirely, restricted to low Earth orbit Shuttles and the odd minimal space robot.

But as seen from 1966… hell, we should be on our way to Alpha Centauri now.

Damn.

I just gave myself a sad.

17 Responses to “2001 as seen from 1966”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Yeah, I remember that. 1988 could have been one hell of a year.

One wonders why the engineers doing the work were so disconnected from the decision-making process that controlled their work.

Now I have a sad also.

Was this from “Space in the Fiscal Year 2001”? I think he also assumed that a rather large chunk of GDP (like 3%) was going to be devoted to spaceflight. Sigh . . . .

Yup!

3% of the fedguv budget for space would *not* have been that big of a chunk of change. NASA’s budget since Apollo has largely been little more than what was needed to keep the lights on (remember, this is a government agency); had it been merely doubled, we could have conquered the whole damned solar system by now. The economic benefits of having such a vibrant high-tech space industry would almost certainly have paid back the added cost, with interest.

Had it not been for the Manhattan Project and the space program we’d still be living a comparatively simple life. Consider life without the computer as we know it, and without teflon!

Now, the trick is to stop paying the lazy to be lazy and give the money to those who will do something useful with it. (Ahem.)

Jim

In one of the essays she wrote on Apollo, Rand said something to the effect that the scientists who innocently expected to be rewarded for their massive achievement with more funding didn’t understand the nature of the system they worked for, a system where reward was based, not on achievement, but on failure. Doubtless if we’d failed in getting to the moon, NASA’s budget would have immediately been doubled.

Want to read his _really_ optimistic space plan from 1948?:

http://www.21stcenturysciencetech.com/articles/Spring03/Ehricke.html

Manned flight to Saturn by 1950…huh?

Have you a link for the paper you describe?

I just read a Wikipedia article on Phobos, prompted by the 2 mentions of missions on the chart. In the article, for whatever Wikipedia information is worth, it appears that Russia, China, Canada, and Europe (EADS Astrium) all have efforts afoot to explore the potato.

I guess we’ll just keep P.R./appeasement and green-whoring covered.

Why did he support fusion power? Was that expected to be available?

> fusion power? Was that expected to be available?

Well, sure. Fusion power has been only 10 years away since the late 1940’s.

Oh, silly me: I should have remembered how soon we’d have it.

Trying to make heads or tails of the dates in that 1948 story shows that it must refer to 2250 or sometime beyond that, or the reason it was unpublished was that it was in need of serious revision.

I’m still trying to figure out why Ehricke was keen on mining Mercury in the 1966 report, because of the huge delta v needed to get anything you mined there to anywhere else in the solar system.

About the only thing I can think of is that he assumed the closer to the Sun you got, the higher on the periodic table the proportions of elements a planet was made of got to be, and Mercury would be a good source of radioactive elements for powering Orion type nuclear spaceships.

The amusingly named Russian Phobos-Grunt spacecraft:

http://www.russianspaceweb.com/phobos_grunt_2010.html#landing

If all those big spheres at the base of the spacecraft look a little familiar, the rocket assembly on the spacecraft is an evolved version of the unmanned Moon lander that did the soil return missions and landed the Lunokhod rovers.

Could Ehricke have been planning to swing around the sun and head back on a slingshot effect?

I was a quite surprised to read about a manned landing on Venus. By 1966 the surface temperature was well known to have been high (that was the time that everyone was re-reading Velikovsky because he’d predicted that temperature).

Absolute! The art of a manned nuclear pulse convoy arriving at Venus and the shielded Orion descending to the Venus surface really put a hook on me when I was a kid.

It was known to be high by 1966, but just how high was still open to question till the Soviet Venera probes probes first entered the atmosphere in 1967 and started showing pressures like those at the bottom of the ocean and temperatures high enough to make lead flow like water.

Before that, all that Earth observations could do was take temperature readings of the cloud tops, and I remember as a kid three different versions of what the surface of Venus was like – one, that it was a vast cloud-covered dry and hot desert; two, that is was a giant cloud-covered hot ocean; and three, that it was something like a giant cloud-covered hot swamp…maybe with dinosaurs living in it*.

At the time it was thought that the clouds would reflect enough sunlight from it to keep the temperatures lower than they would be if it had as little cloud cover as Earth at the same distance from the Sun.

So that max temperatures at the surface would be around, what? 150-175 F at the equator?

* This is of course the one the sci-fi authors loved; and in the “Tom Corbett” books, the big, dumb, and lovable engineer cadet from Venus

– Astro – shoots a T-Rex in the face with a bazooka, blinding it on one side and permanently deforming its face.

I’ve forgotten most of what I might have known about that time. (Anyone who remembers the 60s really wasn’t there.) I wrote off landing on Venus when I realized how much power it would take to get back off the planet.