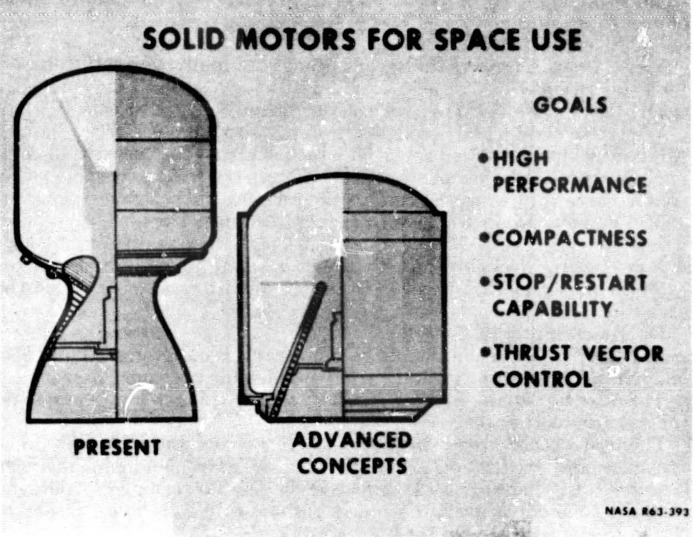

A NASA illustration of an advanced solid rocket motor concept, dated 1963. The most obvious difference between the “present” and “advanced” design was the buried nozzle. By properly shaping the solid propellant grain, the motor would perform normally but with a minimum of unused internal volume; this allowed the motor to be substantially shorter than the conventional design. This would make the associated interstage section equivalently shorter, lighter and cheaper. And by shortening and lightening the interstage, the launch vehicle would be shorter, lighter and stronger, with slightly sturdier structural dynamics.

The advantages of a more compact motor like this are pretty obvious. The disadvantages, maybe less so. The most apparent disadvantage is the *need* for far more advanced materials. That buried rocket nozzle is shown to be quite thin, thinner than the “present” design, yet it would be subjected to horrifying heating rates on *both* sides. There are few materials that could withstand that and retain any sort of structural strength.

Additionally: the desire is shown for thrust vectoring. Numerous options for that are available for the conventional nozzle… but it would be much harder with a buried nozzle. It might be easiest to simply gimbal the entire motor. Stop/restart capability has been achieved with solid rockets, but neither design show here provides for that. It is a non-trivial feature.

The igniter is show to be a small rocket motor suspended within the nozzle, directing it’s exhaust forward into the bore volume of the main motor. Variations on this sort of igniter are quite common for relatively short and stubby upper stage motors such as these.