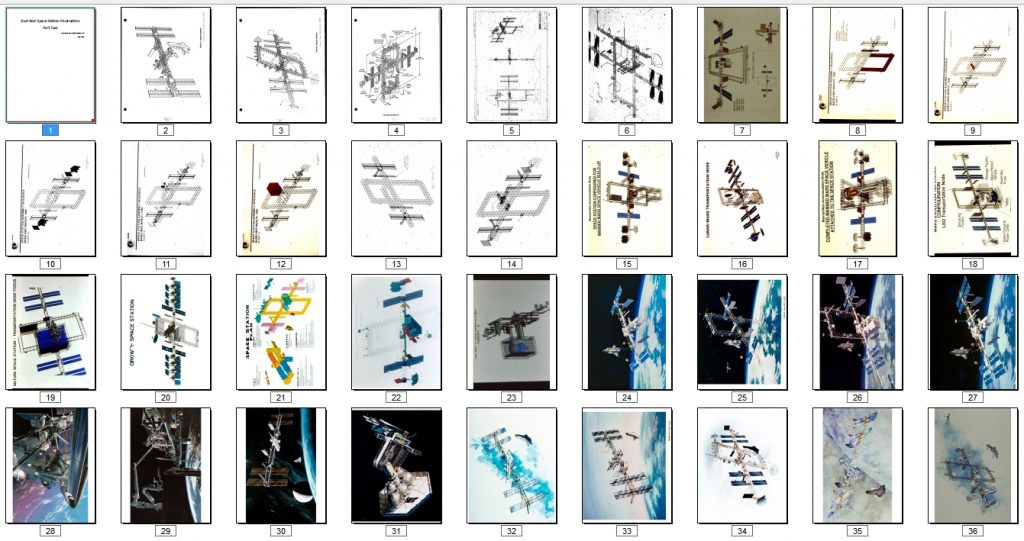

Several days ago word hit of someone with six file boxes of their fathers stuff, wondering what to do with it. Not an unusual occurrence. But in this case, the father was an important engineer at North American Aviation, worked on the XB-70, B-1 and Shuttle, and the files all related to that. In the end, the archive wound up on Craigslist, and sold shortly afterwards. It is now being shipped… to me.

I would not have been able to afford the archive – never mind the shipping costs – on my own. However, by working with the patrons on the APR Patreon , we were able to pool funds so that the total cost per person is *trivial.* When the archive gets here – all 300+ pounds of it – I will go through every single page and catalog it; the best stuff will be scanned and, barring ITAR & classification issues, all of the crowdfunders will receive the complete set of high-rez scans. And then when I’ve gleaned from it what’s worth gleaning, it will be donated to an appropriate archive… the Smithsonian, the SDASM, the National Archives, Edwards AFB, whatever seems best in the end.

The door to sign up for this crowdfunding project is now closed. It followed shortly on the heels of a similar project that scored an admittedly much smaller but definitely fascinating collection of F2Y Sea Dart documentation and diagrams, including much about operational follow-on attack aircraft meant to operate from ships and subs; and a similar archive that was crowdfunded a year or two back that scored a whole bunch of 2707 SST stuff. I’ve grown sick of seeing amazing stuff appear on ebay and then vanish into a black hole, never to be seen by anyone again; this way, aerospace history is preserved and shared.

If you’d like to be involved in this sort of thing, sign up for the APR Patreon and you’ll not only get the monthly aerospace goodies that comes with membership, but you’ll also be able to get in on these crowd funding efforts. You’ll save aerospace history, get a bunch of amazing stuff, and not have to spend a whole lot to do it.