There’s a spaceship on the screen. It is therefore a nerd-priority to determine *everything* about it, starting with “just how big is it?” Of course this exercise could be quickly negated by a simple mention of length on screen or off. But lacking that, we can logic ourselves into a rough estimate.

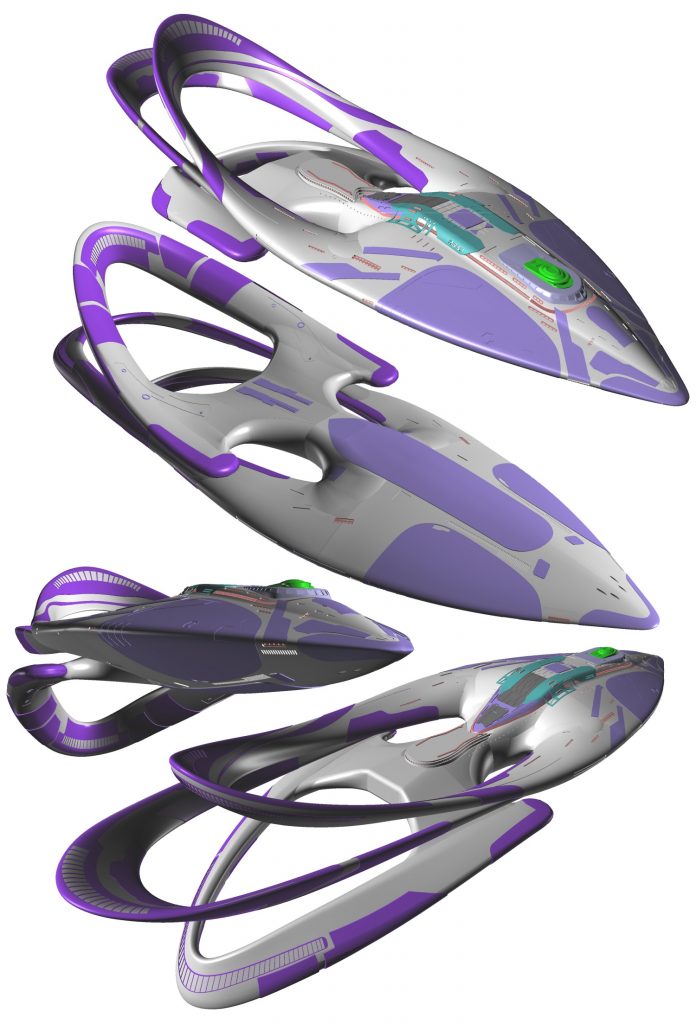

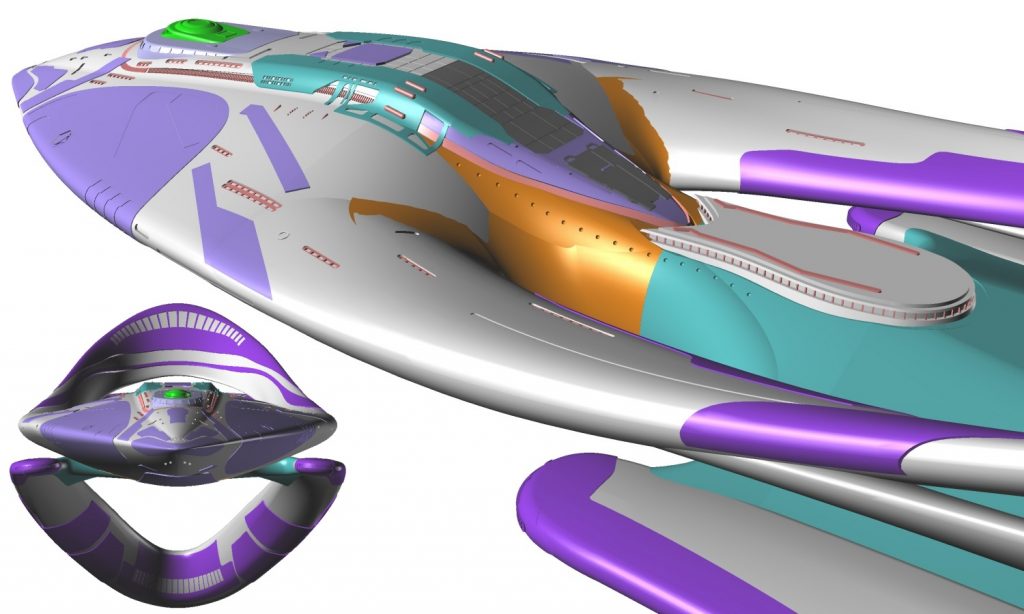

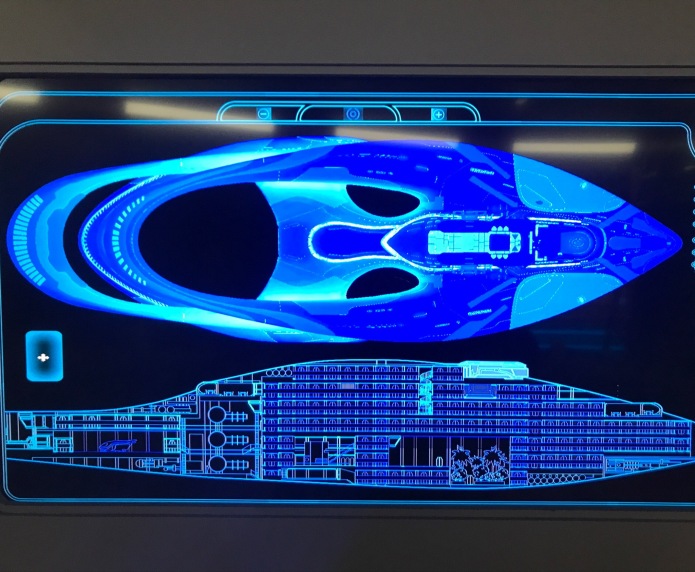

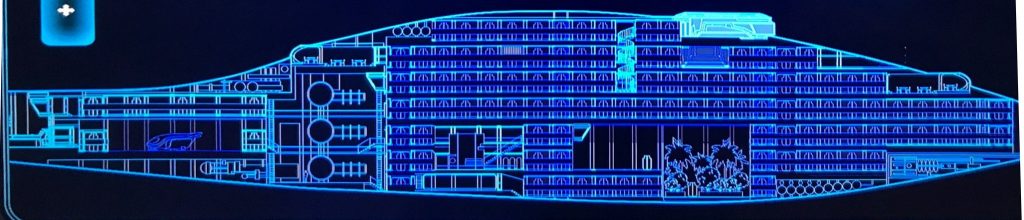

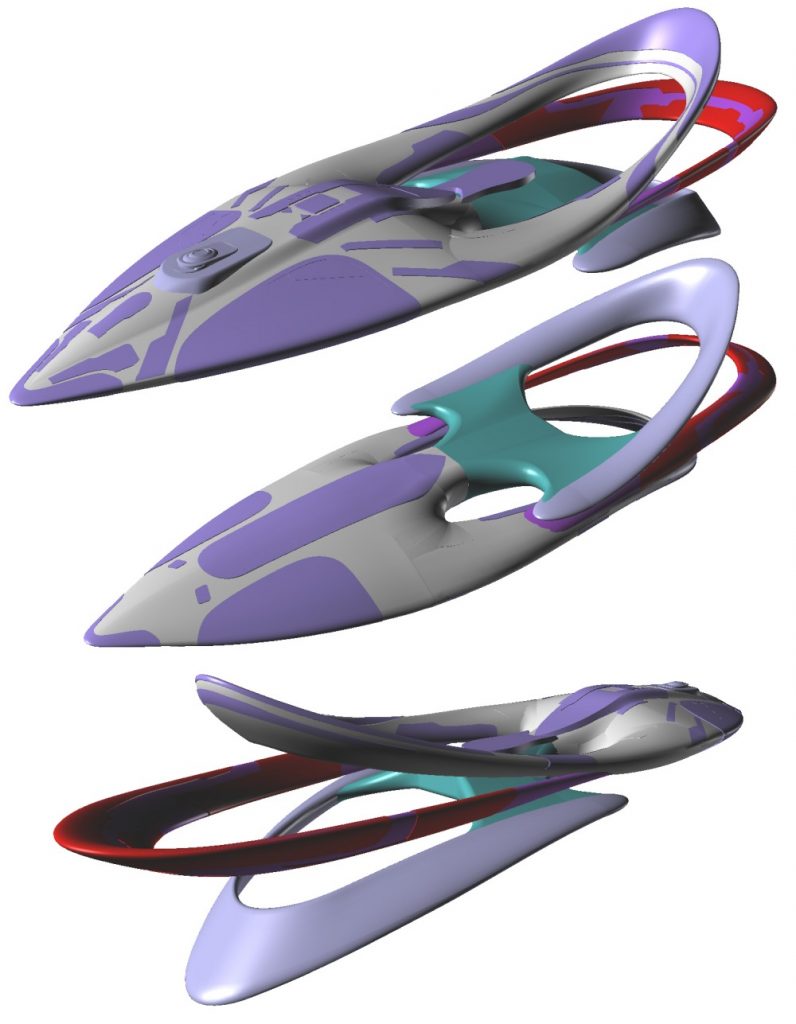

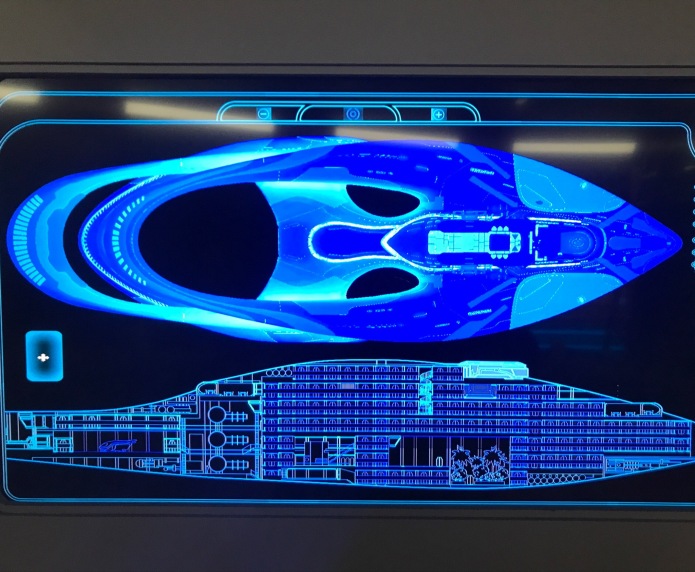

First up, the internet provides two photos that show canon illustrations of the ship, diagrams that appear on display screen on the bridge of the Orville:

The first shows an inboard profile of the main hull with the engine loops; the second shows a top view of the whole ship with a closer view of the cross-section of the main hull. For scaling purposes, that cross section is what we’re after. however, it must be noted right up front that the cross section, canon and used repeatedly on-screen as it is… is WRONG. it must be an earlier iteration of the designs, since there are some meaningful detail differences. The bridge, for starters, is shown further aft that it actually is. And there are lounge “bumps” fore and aft that do not appear on the final design. So it *may* turn out that the interior arrangement could be equally erroneous. However, at this time this is what we got.

Also note that the full side-view marries the 2D-drafted interior profile with what looks like 3D rendered engine loops… loops that are shown not square side-on. So, that’s also less than entirely helpful. but again… it’s what there is to work with.

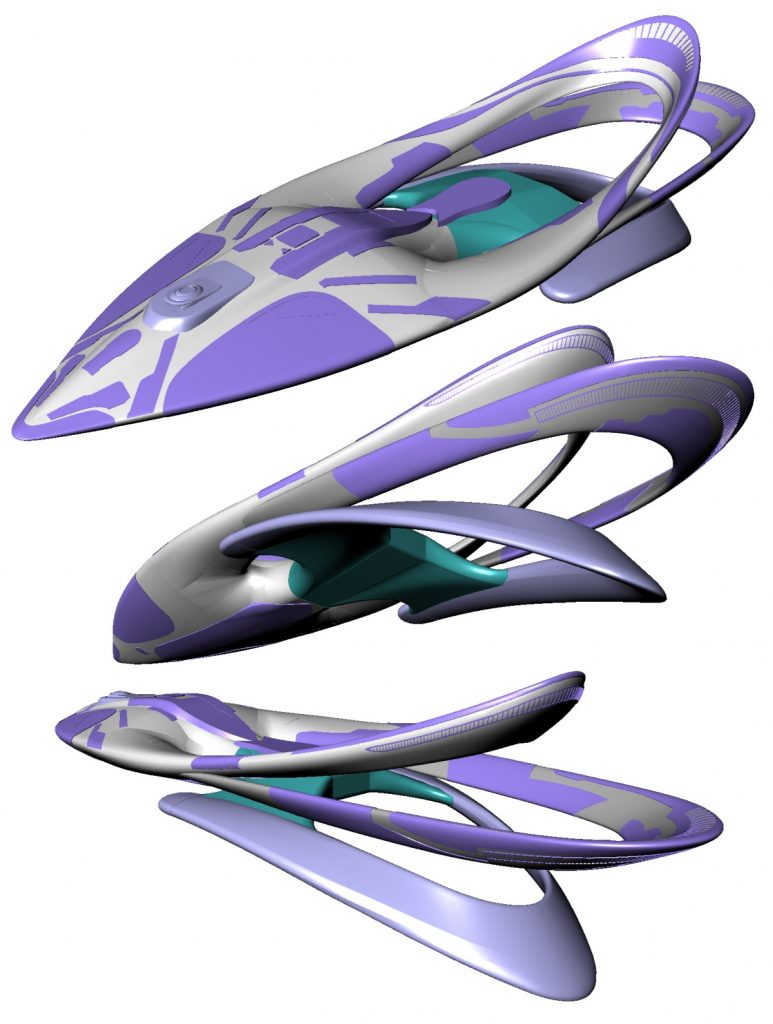

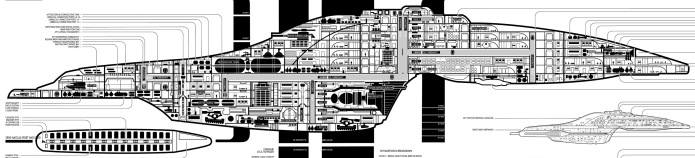

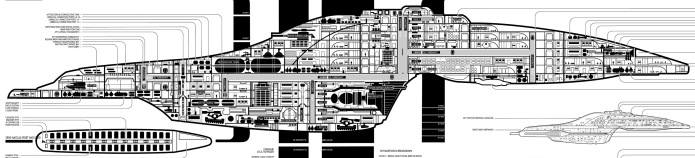

OK, so how to use these images to determine scale? “The Orville” clearly hearkens back to TNG-era Trek for much of the styling. But the Orville is not a major capital ship like the Enterprise was, but a smaller vessel… like Treks Voyager. Fortunately Voyager has been well defined. There are a large number of “master systems display” inboard profile diagrams of the Voyager to pick from, including this one:

The Voyager MSD clearly shows the decks. The Orville “MSD” also shows its decks:

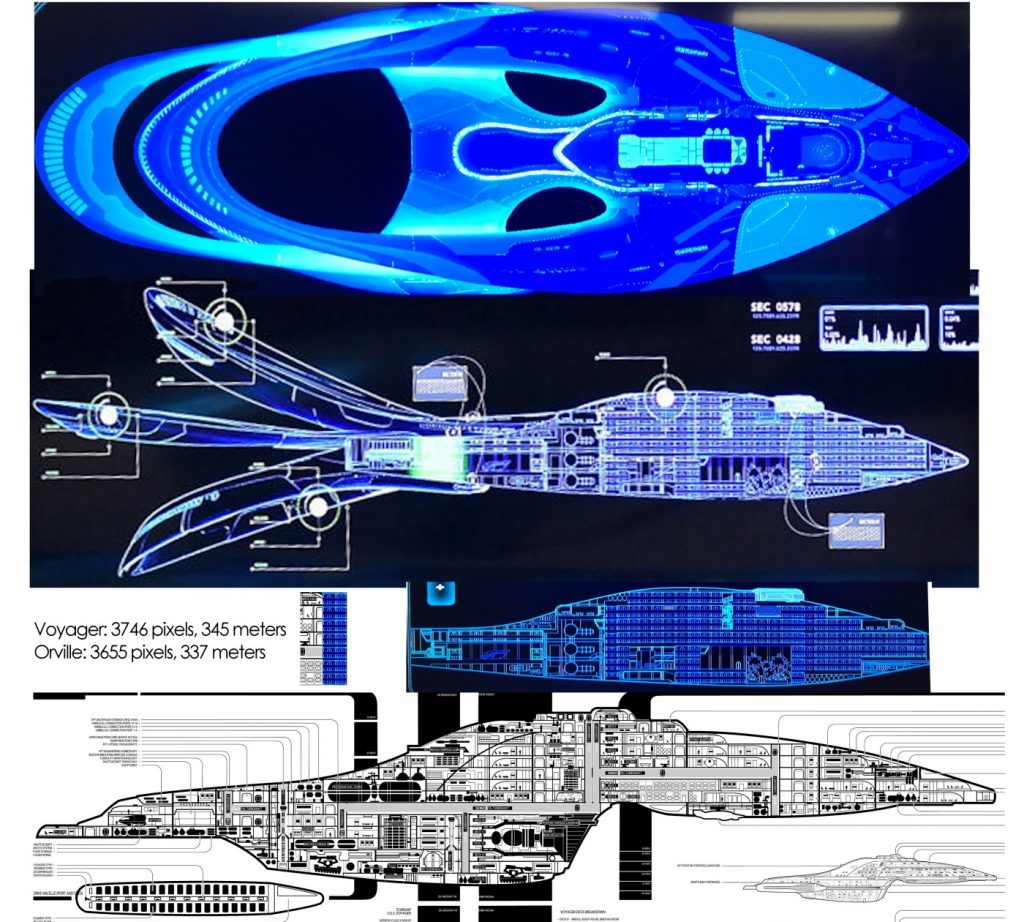

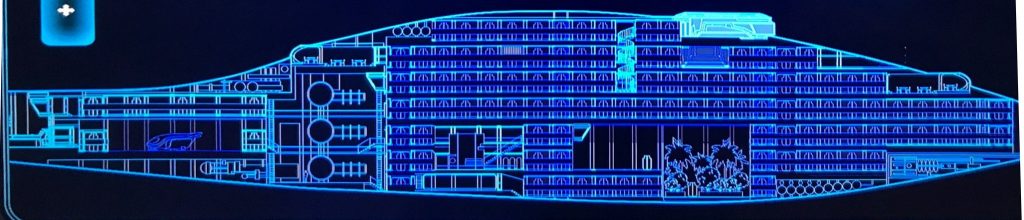

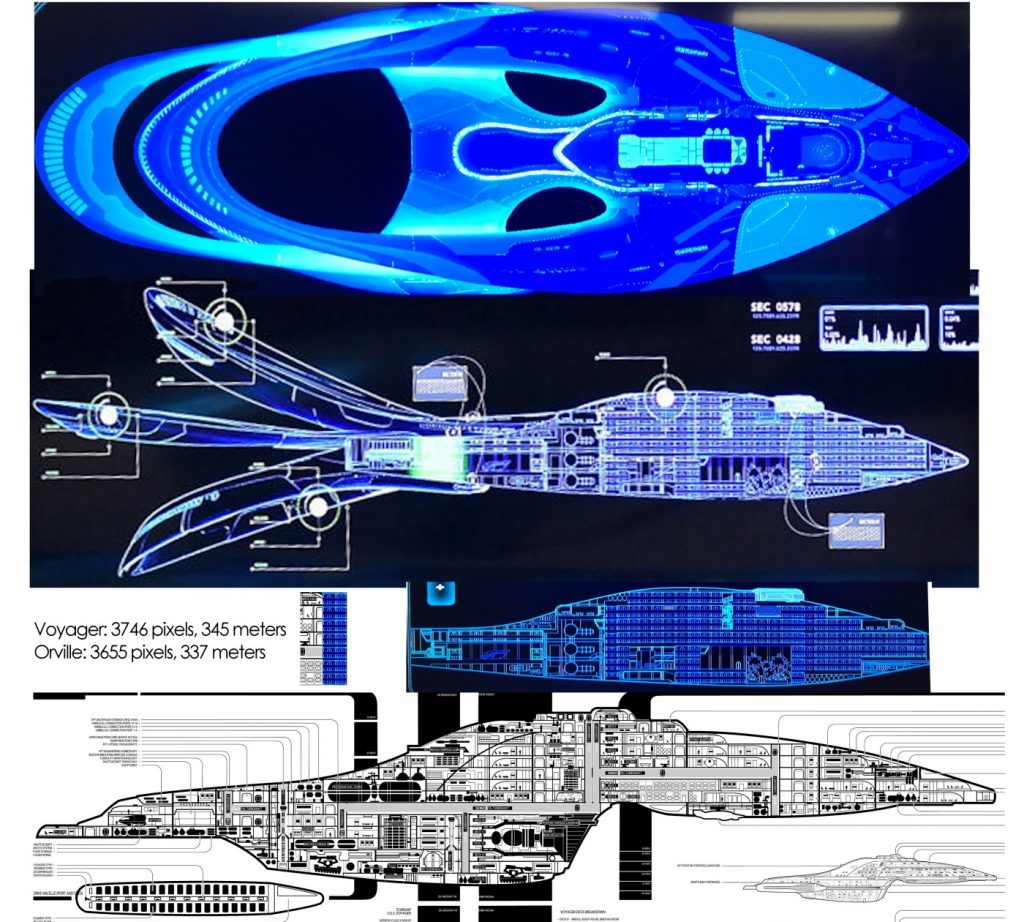

It’s by no means certain that the Orville uses the same spacing between decks that Voyager did… but again, it’s the best assumption that can be made at this time. So, the thing to do is to take the decks of the known-quantity-Voyager and scale the decks of the Orville to line up, like this:

Once you’ve scaled the Orville diagrams to match the deck-scale of the Voyager diagram, everything lines up looking like this:

And what this results in is the Orville being *really* close in length to the Voyager… 337 meters for the Orville, 345 meters for Voyager. I don’t know if this was intentional on the part of the shows producers, but it wouldn’t surprise me if there’s an in-joke here that the Orville is supposed to be exactly the same length as Voyager.

So for now, and until I see something better, I’m going with a length of 337 meters for Orville. Given the lack of a “secondary hull” the Orville thus seems to have substantially less internal volume than Voyager, so probably a smaller crew. But interestingly the Orville is *much* faster than Voyager. In the episode “Pria” it is claimed that Orville can fly at 10 light years per hour. If it was suddenly dumped 70,000 light years from home as Voyager was, it could fly home in 7,000 hours… 291 days. “The Orville” could thus copy the “ST:V” model by having the ship tossed to the other side of the galaxy – say, a season finale – and could wrap things up entirely within the next season. When the Orville gets back to Earth, rather than being met with celebrations, it’s met with “where the hell have you been? You’re late.”

Sanity check – a comparisons of the lounges and shuttlecraft between the two ships:

Looks about right.