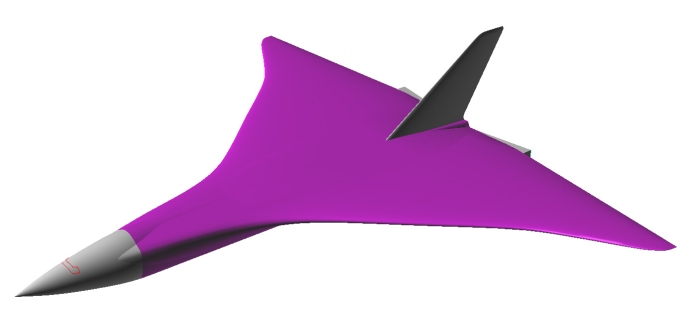

A 3D CAD model currently being constructed o the Rockwell “Star Raker.” This is being done in order to nail down diagrams and artwork for a future issue of US Launch Vehicle Projects… and also possibly to serve as the basis of a 1/288 scale model kit.

SpaceX just launched and recovered a Falcon 9 booster for the third time, after previous launches in May and August. Additionally, the upper stage has reached the intended orbit and will begin spitting out its payload of 64 small satellites. Most famous of these is the infamous “Orbital Reflector,” an “art project” designed to annoy astronomers.

Remember when recovering a rocket *once* was big news?

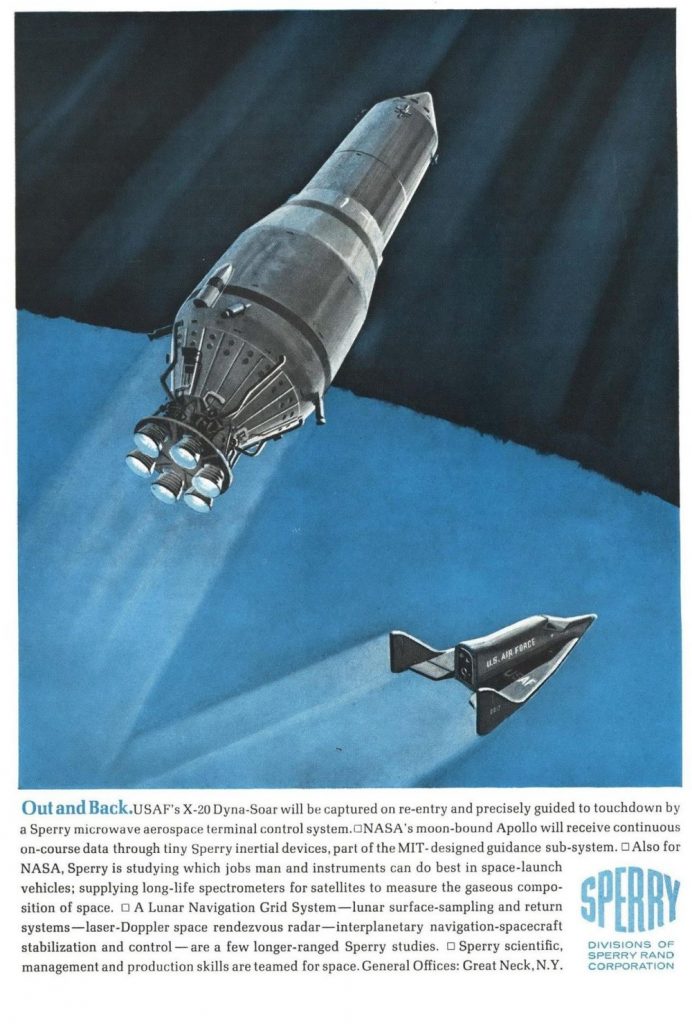

A magazine ad from 1963 showing the S-IV stage and the X-20 Dyna Soar. The Dyna Soar is shown without its adapter section and Transtage, indicating that it is approaching re-entry (note that it is shown with the canopy heat shield still in place). The Saturn S-IV stage, used on a few Saturn I launches, was smaller than the S-IVB that was used on later Saturn Ib and Saturn V launches, and used six RL-10 rocket engines instead of the S-IVB’s single J-2. Also note the three prominent “ullage rockets” sticking out from the base of the stage. These were small solid rocket motors that would impart a slight forward acceleration to the stage prior to the ignition of the RL-10’s. The acceleration would be high enough and last long enough to settle the propellants into the rears of the tanks. Otherwise the liquid propellants would float around in microgravity and might very well not feed properly into the plumbing system; if a turbopump swallowed a large bubble of gas rather than liquid, it could be destroyed.

The Saturn I/S-IV never launched an actual Apollo CSM, but only boilerplate test articles. Interestingly, the BP-16 test article, launched May 25, 1965, stayed in orbit until July 8, 1989.

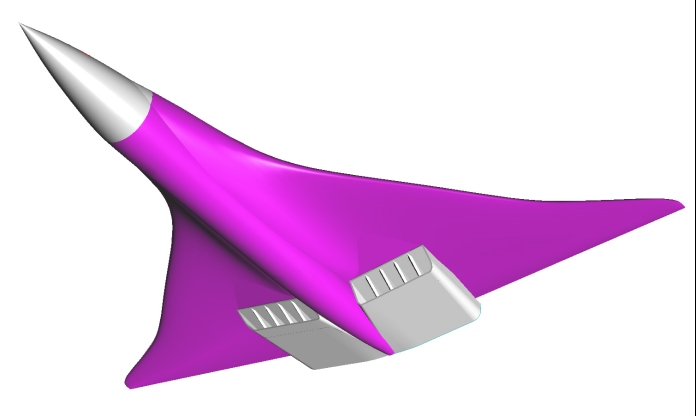

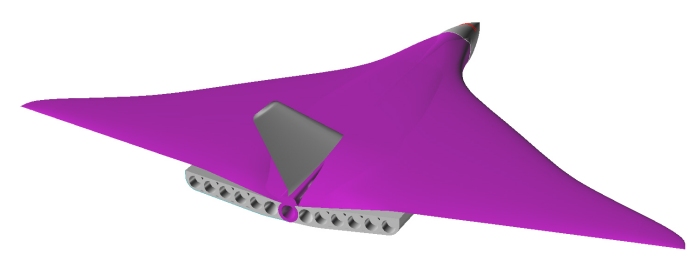

A design circa 1970 for a Lockheed lifting body space shuttle concept. This design was derived from the earlier STAR Clipper stage-and-a-half design from the late 1960s… the whole story of the STAR Clipper and its many derivatives is given in Aerospace Projects Review issue V3N2, available HERE.

Note that this vehicle is equipped with sizable internal propellant tanks. As a result the cockpit is separated from the payload bay; in order to access the payload, the crew would need to pass through a long, narrow tunnel not unlike that within the B-36 bomber.

A Dow Corning magazine ad from late 1969 by famed and prolific space artist Robert McCall illustrating a nuclear-powered artificial gravity space station. It’s a nifty painting, the original of which was apparently given away in a contest; all entrants were apparently given a full color print of the artwork.

Another copy of it:

On the one hand, SpaceX has announced the date for their first planned unmanned launch of their manned Dragon spacecraft to the ISS: January 7, less than two months from now. If that works… then SpaceX will be on track to restore Americas ability to launch our own astronauts back into space. Yay! On the other hand…

Reefer Madness at NASA

In short, NASA has apparently flipped out after seeing Elon Musk,away from work, away from SpaceX property, and on his own time, smoke some weed and drink some booze. So they’re conducting safety reviews of both SpaceX and Boeing, focusing on their “workplace safety cultures.”

In that same spirit, I hope they run a similar review of themselves. I’ve heard tell that astronauts sometimes like to get tore up on their free time.

I suspect that a *lot* of this is n effort by the entrenched Old School to get into spaceX to get them to change their culture to be more Old School.

What is going on with SpaceX and all these Big Falcon Rocket changes?

The design of the BFR has apparently undergone yet another radical change, as-yet undefined. Additionally, the first stage is now called the “Super Heavy” and the upper stage is the “Starship” because Musk claims future versions will indeed go beyond the solar system. Ummm.

On one hand, it’s great that SpaceX is fast on its feet, changing the design as much as needed, as needed. It is of course perfectly normal while devleoping major new designs for there to be a long protracted period of constant design changes, sometimes including radical changes in direction. Take, for example, the long and winding paths Boeing took to the develop the B-52 and B-59 bombers.

On the other hand, it often seems as though these changes of course are driven by personal whim, and every time there’s a redirection there are major delays. This will make even *pretending* to keep to the schedule SpaceX has laid out problematic at best. The upper stage – now “Starship” – is supposed to make test hops in 2019. Hard to do if they’re still designing the thing.

But… SpaceX isn’t NASA. They just might be able to perform.

Note: I’ve been a bit dubious about this one. While I’m all in favor of as many Western billionaires as possible spending their money on launch systems, spacecraft and space propulsion systems (and even more in favor of some such billionaire paying *me* to study such things… anyone? Anyone?), the LauncherOne seems like kind of a “meh” approach. Simply a modernized Pegasus in many ways… and Pegasus was by nobody’s definition an innovatively inexpensive way to send a whole lot of stuff into space. Still… the more the merrier I suppose.

Here’s some more “Humans R Teh Dum” for ya…

When Space Science Becomes a Political Liability

Basically, it is easy to play off the “don’t spend money in space when there are still problems on Earth” trope, as exemplified by this attack ad:

Fletcher, the candidate who campaigned against an opponent based on his support of space science, won. Her district? Houston, Texas. Gee, I wonder if there might be any of that nasty space-spending going on in Houston?

It boggles my tiny little mind that anti-space worked so well in a town with a major NASA center. This does not bode well for the future. However… done right this *could* be used to argue that as NASA winds down in relevancy, with space exploration becoming the province of private enterprise, perhaps the space centers of the future could be located elsewhere. While it is down to physics that launch centers should be as far south as practical, that’s not even remotely true for *other* centers. Manufacturing, testing, laboratories, planning, admin, mission control… these could be *anywhere.* Like a dream I had a while back, manufacturing of the spacecraft and launch systems of the future could be done *anywhere.* With boosters and spacecraft like the BFR, they could be built one place far from the launch site… and could self-transport themselves from the manufacturing facility near, say, Bozeman Montana to the launch facilities in Florida. This ability would allow for the location of major space centers in places that are not only substantially less Hell-like than Houston with it’s insane heat and humidity, but also where the citizenry actually appreciates them.

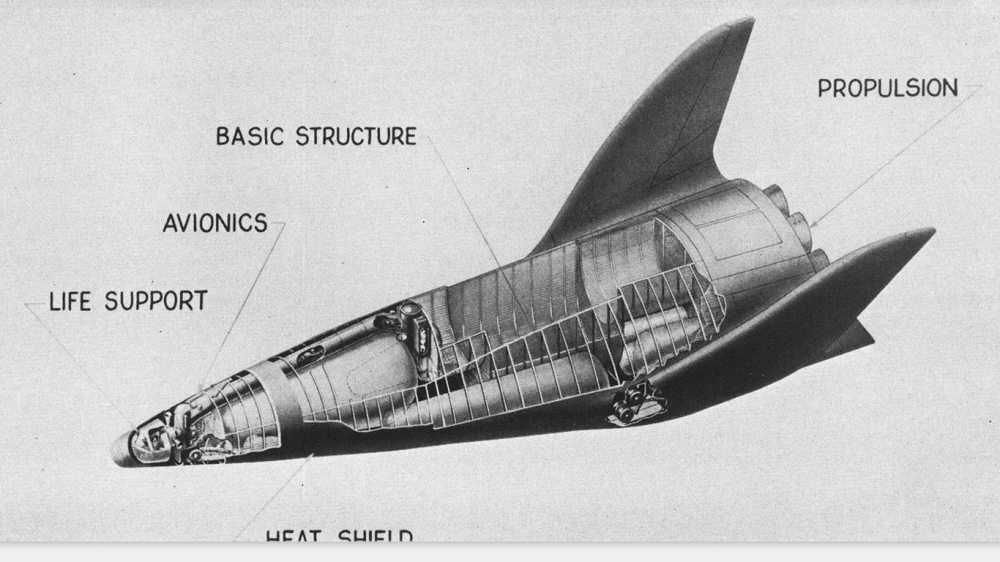

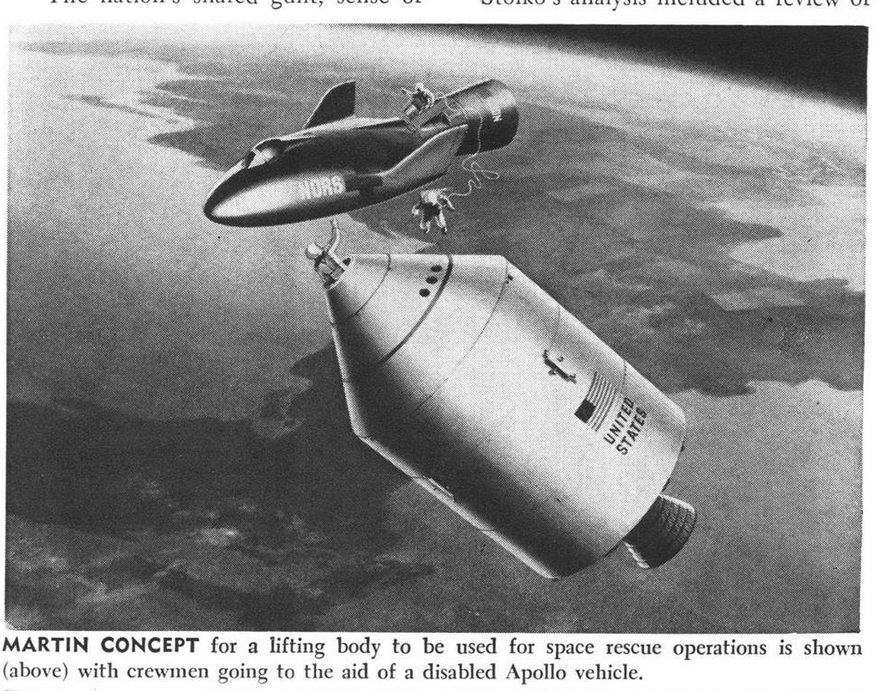

The 1969 movie “Marooned” featured an Apollo crew stranded in orbit and eventually rescued by a lifting body spacecraft,the fictional “XRV.” It has been noted that the vehicle and the basic setup look a *lot* like an illustration from a 1965 issue of Aviation Week depicting a Martin Co. lifting body rescuing the crew of an Apollo spacecraft:

There is clearly something a little strange going on in this artwork: what may seem like an adapter section or a propulsion module behind the lifting body is actually a docked Gemini spacecraft. There is no explanation for this, but I can speculate. The lifting body is meant to serve as a rescue craft, so it would need to have as much internal space as possible. Not just for three rescued Apollo astronauts, but three astronauts potentially in medical distress. So they might need to be laid out on stretchers, not just sitting in seats. Consequently, while they would need a pilot to get them home and “ambulance staff” to get them squared away, there might not be enough room for everyone. So *perhaps* what’s going on here is that the spaceplane is launched empty or with just a pilot, and the Gemini/Adapter has two EMTs in it. They get the rescuees dealt with and sent home, and they come home in the Gemini. This way, three rescuers go up, but only one comes down taking up space in the lifting body. This is non-optimal, of course; better would be to bring everyone home in one large vehicle. But perhaps this was the best that could be done with the intended launch system, presumably a Titan IIIc.

The lifting body is clearly related to the X-23/X-24 geometry that Martin was beginning to study at the time. A mockup that is very similar, though with the central vertical stabilizer that eventually appeared on the X-24, is shown HERE and HERE.