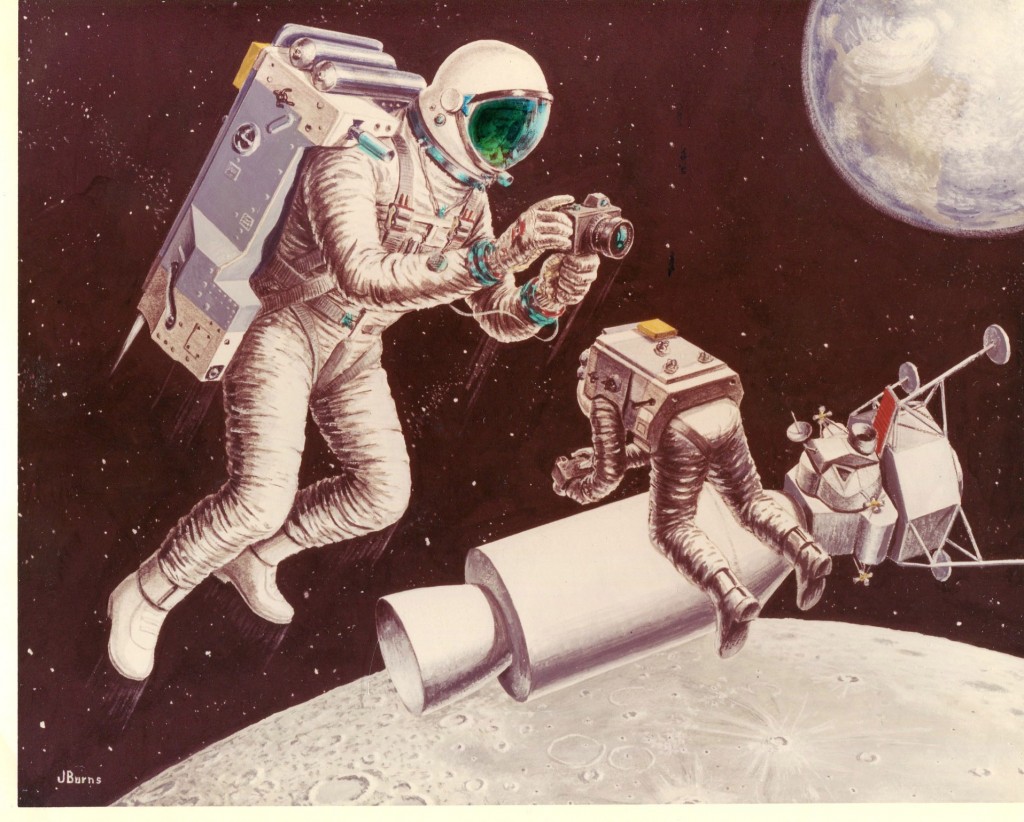

An RCA concept from some time in the 1960’s for an astronaut maneuvering unit that was to use voice controls. This would negate the need for hand controls, but it seems unlikely that 1960’s technology was quite up to the task. Image from HERE. Note that while the backpack is depicted in some detail, the Apollo spacecraft in the background is quite inaccurate and minimally detailed.

In the innumerable CAD diagrams I’ve created and will – presumably – continue to create, I often include a simple human figure to provide a sense of scale. But the same figure, repeated over and over… well, that’s kinda boring. So, who has alternates? I’m looking for simple line drawings (DWG or DXF or some other vector format would be easiest, but GIF/JOG/whatever would be fine too) of human figures that would look good standing next to aircraft, spacecraft, launch vehicles, ordnance, etc. Please feel free to post pics and links on the comments.

I’ve posted another “PDF Review” over at the APR blog, this time on a 1967 Convair publication on the Atlas family of launch vehicles. This document was originally found on NTRS… but it doesn’t seem to exist there anymore. I’m guessing it was a victim of the March, 2013, lobotomy that NTRS underwent.

PDF Review: “Advanced Atlas Launch Vehicle Digest”

I have the full PDF file available for download over yonder. If this proves of interest and/or value, please consider participating in my Patreon campaign.

“Only people who hate cats refuse to donate to the APR Patreon. You don’t hate cats… do you?”

“Only people who hate cats refuse to donate to the APR Patreon. You don’t hate cats… do you?”

As the OPEC oil embargo of the 1970’s ground down the American economy and jacked up the cost of transportation, many studies were made of alternative propulsion systems. For cars and buses and the like, electrical systems were at least theoretically feasible, though even today fully electric ground transport remains problematic. But electric aircraft were out of the question. Similarly, jetliners could not be retrofitted to burn coal or wood, or run off solar power. So that limited the options. One available option was liquid hydrogen. Long since proven on rockets, liquid hydrogen had been used to power jet engines in an experimental capacity. In theory it makes great jet fuel… lots of energy, and produced with no need of oil whatsoever (a nuclear reactor and an electrolysis system can do it, though there are more efficient means). But there were two major down sides: it’s a serious cryogen, requiring vacuum dewars for storage, and the density is pathetically low. Thus a jetliner would need fairly gigantic fuel tanks.

Lockheed of course studied the idea, using their last commercial airliner, the L-1011, as the basis. One concept called for giant fuel tanks to be carried on the wings, making the plane look almost like three aircraft flying in close formation; another idea was to stretch the fuselage and insert propellant tanks in front of and behind the passenger compartment. This would of course separate the passengers from the pilots. Also studied was the same idea but for an L-1011 freighter, artwork for which is shown below.

The idea would have almost certainly worked. But it would have been a logistical headache of the worst kind. None of the existing airport refueling infrastructure would have been usable, and the crews would have to be especially trained. Jet fuel can be stored in simple tanks; liquid hydrogen needs much more careful management to minimize boiloff.

Years ago when I worked at ATK on the Ares I and Ares V booster programs, I put forward an idea. It was a simple and, I thought, fairly obvious notion, based on a few facts:

1) Weight growth is generally to be avoided in space launch. However, if the weight gained is on a booster stage rather than an upper stage, the performance penalty is much reduced.

2) Not every flight would make full use of a launch vehicles potential. Given that propellant is essentially free, compared to the rest of the costs involved, it makes sense where possible to carry extra payloads if you can.

3) A secondary payload on the booster stage is, these days, of minimal interest, but would also be minimally payload-impacting

So here was my idea: on launches of the Ares V booster that did not make full use of the launch vehicles potential, carry “parasite” payloads on the solid rocket boosters. The payloads I had in mine? Paying passengers. The idea would be to put a capsule, or perhaps something akin to Space Ship One (fat fuselage with just enough wing to fly and land), on the nose of the booster. Just after booster separation, the capsules would themselves separate from the boosters.

Since they would be very distinctly sub-orbital, heating issues would be relatively trivial. Since the flight duration would be only a few minutes, onboard life support would also be minimal. As a result, the capsules could be spacious, relatively lightweight, and equipped with *big* windows.

If each booster carried a capsule, and each capsule seated ten passengers, and each passenger paid, say, $100,000, then each flight would generate an extra $2 million. Not much considering the probably $1Billion price tag of each launch, but hey… why not? Some launches could charge more, such as historically important flights to the Moon or Mars or such. How much would *you* have paid to hitch a ride alongside Apollo 11, for example?

And what would the passengers have seen? Lessee:

[youtube 2aCOyOvOw5c]

Needless to say, they didn’t think much of my idea. Grrr.

(Is this post a repeat? Maybe. Seems like I’ve yammered about this before. oh well.)

Found on ebay, an artists impression of a Hamilton Standard concept for a one-man rocket propulsion system for use by lunar explorers. Dating from 1964, this is a “rocket belt” similar to that built and flown by Bell. The lack of atmosphere would give the rocket nozzles better performance than in Earths atmosphere, and the lower lunar gravity would mean that lower thrust would be needed. Still, performance would likely have been rather disappointing… at best a few minutes of thrust.

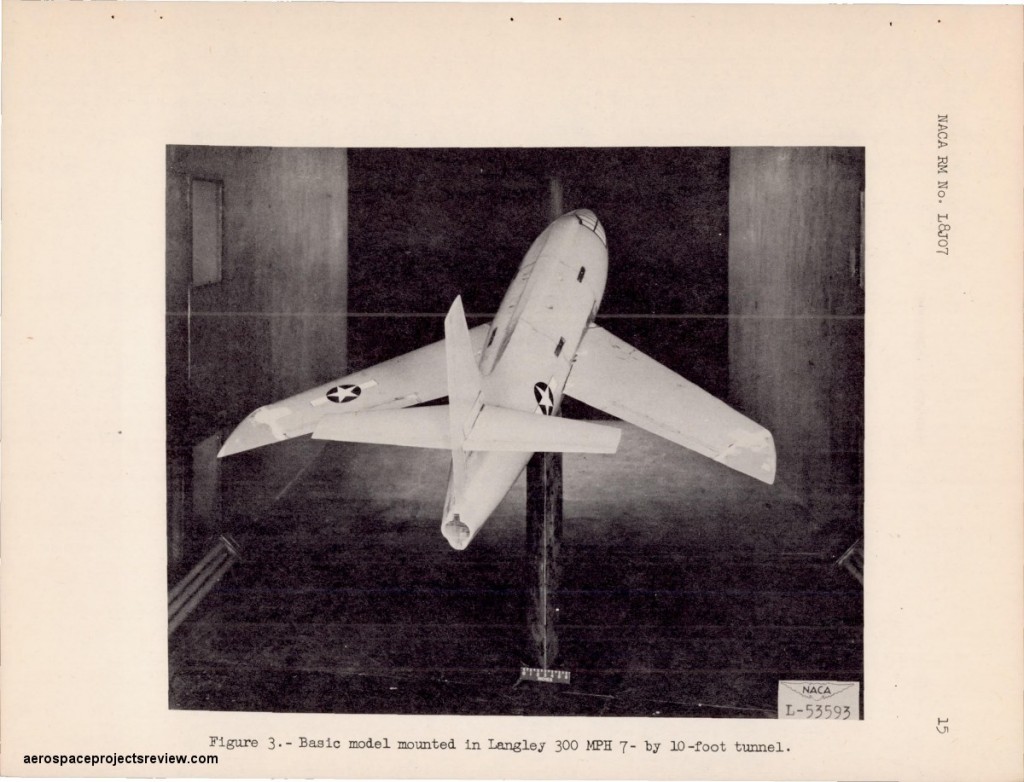

I’ve posted another PDF review over at the APR blog, this time on NACA wind tunnel testing of a swept-wing X-1 configuration.

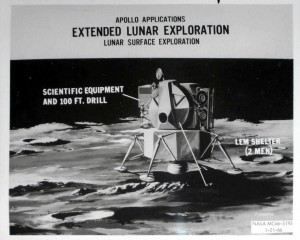

Found on ebay, a bit of NASA promo art depicting a 1966 Apollo Applications Program concept for a LEM Shelter. This would have been a more or less stock descent module with an ascent module without the ability to ascend. It would thus have been capable of transporting more cargo to the surface, including a habitat better capable of supporting a crew for a week or more. Transport back up to lunar orbit would have been accomplished via another LEM.