There was a time when American auto manufacturers had important aerospace divisions. Chrysler, for example, was responsible for rockets such as the Redstone, Jupiter and the Saturn I and Ib first stage.

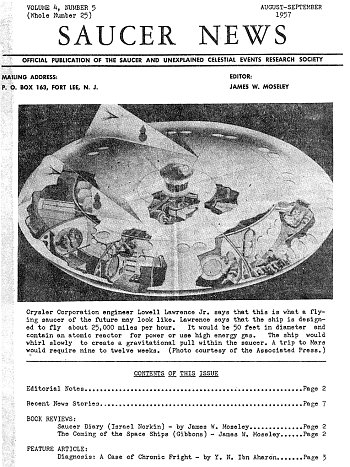

In late 1956, Lovell Lawrence Jr, an assistant chief engineer at the missiles division of Chrysler, publicized a concept for a nuclear-powered “flying saucer.” It seems to have been *partially* a reasonably rational concept for a long duration spacecraft for missions to Mars. It would spin like a frisbee to generate artificial gravity, though the relatively small radius would be likely to produce some harsh Coriolis effects. The saucer would be about 50 feet in diameter and only 6 feet thick.

Where the design goes a bit off the rails is that the performance expected of the craft was insanely impressive. It was a single-stage-to-solar-orbit craft, capable of taking off horizontally from a runway using nuclear-powered jet engines (note: “jet” in this case might mean “rocket.”) The craft would be capable of going from the Earth to Mars in 9 to 12 weeks.

Being that close to an atomic reactor (with a light enough shield to allow the thing to take off) would be a death sentence long before the craft would get to Mars.

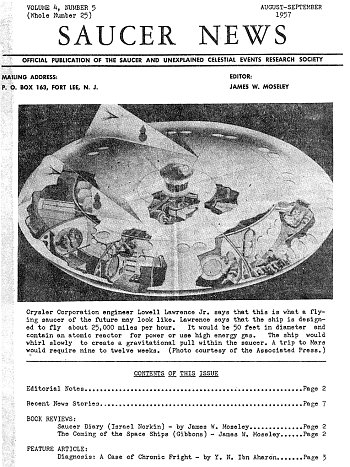

After years of trying to research this concept, all I’ve managed to scrape up are three things from Ye Olde internet: two newspaper articles and one cover story from a UFO “fanzine.” I have tried over some years to obtain a copy of the “Saucer News” from August-September 1957 from sites like ebay, but without success. It seems like an original printing, or at least a decent scan, would provide a reasonably good version of the Chrysler saucer art. Anybody has more on this, I’m interested.